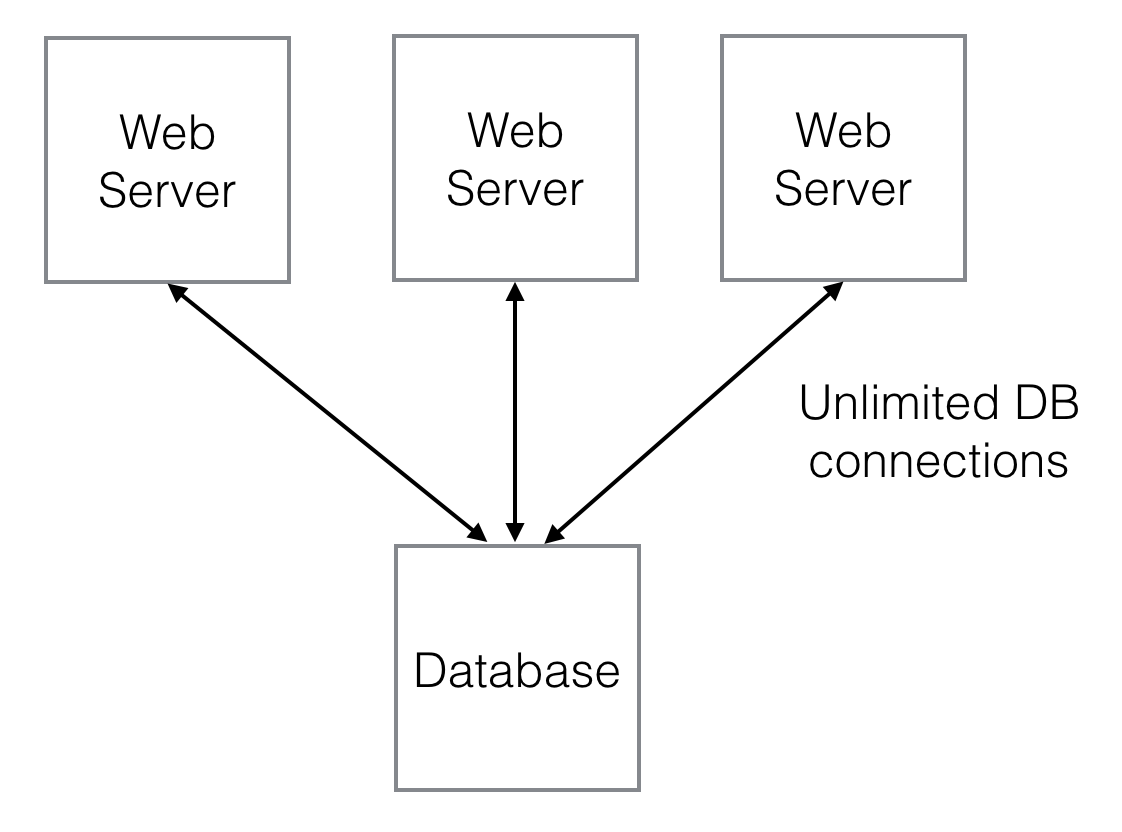

Whenever we have a limited resource in a system, we need to be careful not to overload it. The canonical example of this is a database in web application. We can scale a web application horizontally by building more web servers, but with relational database we are usually limited in the extent to which we can scale the database, at least with respect to writes. This is an oversimplification, and there are some workarounds (e.g. mutiple read slaves, sharding, etc.), but there is always going to be some part of a distributed system which is harder to scale.

So, if we scale our web application by building more webservers, that means more and more reads and writes hitting our database server, and eventually we will hit a limit and our whole web application will stop responding.

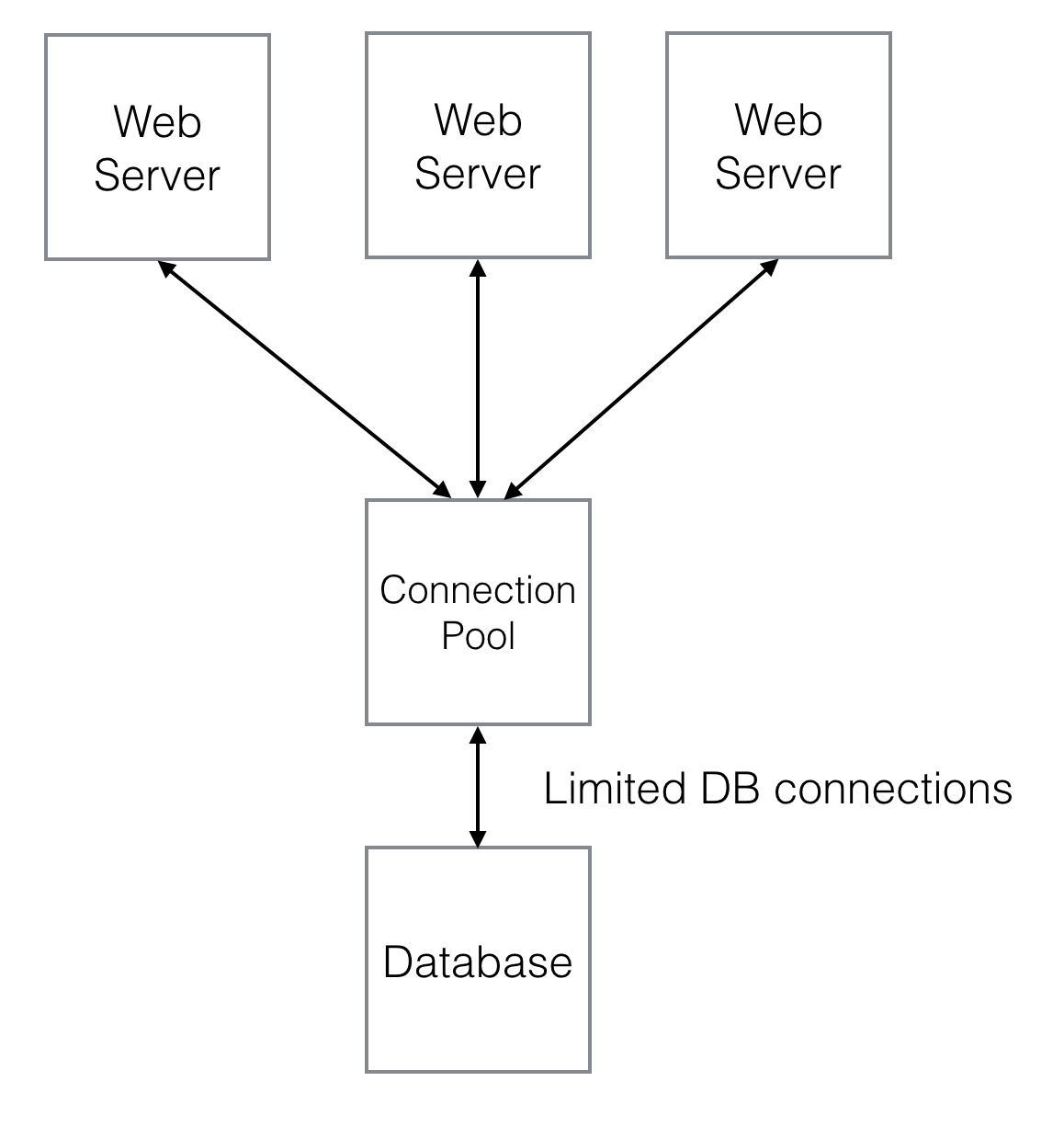

Using a worker pool is one way to limit the load on our scarce resource. In this scenario, access to the database is forced through a bottleneck that we create, such that we will never have more than N workers reading or writing to the database simultaneously, rather than every web session having its own connection.

By limiting the number of workers, we can set a limit on the load on our database, such that it should never freeze up completely. Here, we’re trading system responsiveness for stability. Anytime more than N database operations need to happen at once, web requests will block until a database worker becomes available to service the request. So our application will become less and less responsive as load increases, to the point where invidual web requests may time out. But, the system as a whole should continue to do useful work.

In the Erlang/Elixir world, the most common way to manage a worker pool is by using the poolboy package. Here is a quick example of how to use it.

First, we need an application, and a worker.

$ mix new poolboy_example

$ cd poolboy_example

Now, create lib/my_worker.ex with the following contents;

1 defmodule MyWorker do

2 use GenServer

3

4 def handle_call(:do_work, _from, state) do

5 IO.puts "process #{inspect self} doing work"

6 :timer.sleep 1000

7 {:reply, "response", state}

8 end

9 endThis creates a very simple worker process, implemented as a GenServer which exposes a single :do_work function. The worker will always return the string "response" to the caller, and the :timer.sleep is just there to simulate doing work which takes some time.

As you can see on lines 4 and 7, the current state of the process comes in as a parameter of the handle_call function, and is the last element of the :reply tuple.

In Erlang/Elixir, processes maintain state by sitting in a loop that blocks waiting for incoming messages. After handling a message, the process recurses back into the loop, passing in the (possibly modified) state.

The Elixir GenServer behaviour takes care of the loop for us, so we just have to implement the methods we care about in our specific process. We don’t care about the state of the process in this example, but in a database worker the state would probably contain the database connection.

Here is how we can use our worker;

1 $ iex -S mix

2 iex(27)> {:ok, pid} = GenServer.start_link(MyWorker, nil)

3 {:ok, #PID<0.236.0>}

4 iex(28)> GenServer.call(pid, :do_work)

5 process #PID<0.236.0> doing work

6 "response"

On line 2, we create our worker process, passing in nil as the starting state.

Let’s simulate some simultaneous requests hitting our application. Edit a file called without_pooling.exs, and add the following;

1 defmodule Demo do

2

3 def call do

4 {:ok, pid} = GenServer.start_link(MyWorker, nil)

5 GenServer.call(pid, :do_work)

6 end

7

8 end

9

10 tasks = Enum.map(1..10, fn(_) ->

11 Task.async(fn -> Demo.call end)

12 end)

13

14 Enum.each(tasks, &Task.await/1)Demo.call creates a new worker process and calls do_work. Lines 10-12 set up 10 asynchronous tasks, each of which invokes Demo.call, and then line 14 waits for all the tasks to finish - otherwise the script (and all the workers, which are children of the script process) would terminate before any of the workers have responded, and you won’t see any output.

NB: At this stage, there isn’t much point in MyWorker being a GenServer - we could just expose a public do_work function and call MyWorker.do_work in Demo.call - but we want the workers to be GenServer processes when we add poolboy, so I’ve made it a GenServer from the start.

Let’s run the script;

$ time mix run without_pooling.exs

process #PID<0.127.0> doing work

process #PID<0.128.0> doing work

...

process #PID<0.135.0> doing work

process #PID<0.136.0> doing work

real 0m1.575s

user 0m0.475s

sys 0m0.215s

Each do_work call was handled by a different process, and all of them executed in parallel, so the whole script finished in a little more than one second.

Now let’s use a pool with a limited number of workers.

We’re going to use poolboy so we need to add it our project. Open up the mix.exs file, and find the dependencies section;

defp deps do

[]

endNow alter it to look like this;

defp deps do

[{:poolboy, ">= 1.5.1"}]

endSave it and tell mix to update the project’s dependencies;

$ mix deps.get

We need to make a slight change to our worker, to make it play nicely with poolboy. Edit lib/my_worker.ex and add the following lines;

def start_link(_) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, nil, [])

endNow edit with_pooling.exs and add the following;

1 defmodule Demo do

2

3 def call(pool) do

4 :poolboy.transaction(pool, fn(pid) -> GenServer.call(pid, :do_work) end)

5 end

6

7 end

8

9 {:ok, pool} = :poolboy.start_link([worker_module: MyWorker, size: 2, max_overflow: 0])

10

11 tasks = Enum.map(1..10, fn(_) ->

12 Task.async(fn -> Demo.call(pool) end)

13 end)

14

15 Enum.each(tasks, &Task.await/1)We’ve changed Demo.call so that it uses :poolboy.transaction to send the do_work call to our pool of workers. The pool itself is created on line 9, and the rest of the script is almost the same as before. Let’s see what happens when we run it;

$ time mix run with_pooling.exs

process #PID<0.120.0> doing work

process #PID<0.119.0> doing work

...

process #PID<0.120.0> doing work

process #PID<0.119.0> doing work

real 0m6.049s

user 0m0.560s

sys 0m0.306s

This time you should see the output appearing two lines at a time, and the total runtime is a bit more than 5 seconds (10 calls, with 2 being serviced at a time). Also, notice that only two different PIDs appear in the output, because our pool of two worker processes is being created once and then reused for each subsequent call.

The code for this example can be found here